Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

The AutoimmunityCare IBS Bundle is a clinically formulated, gut-healing supplement protocol designed to target the root causes of Irritable Bowel Syndrome — not just symptoms. This bundle supports digestion, reduces bloating, calms inflammation, restores microbial balance, and strengthens the gut lining. It combines premium probiotics, digestive enzymes, gut-lining nutrients, and anti-inflammatory botanicals to help you regain digestive comfort and restore healthy bowel patterns.

Understanding Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Comprehensive Guide

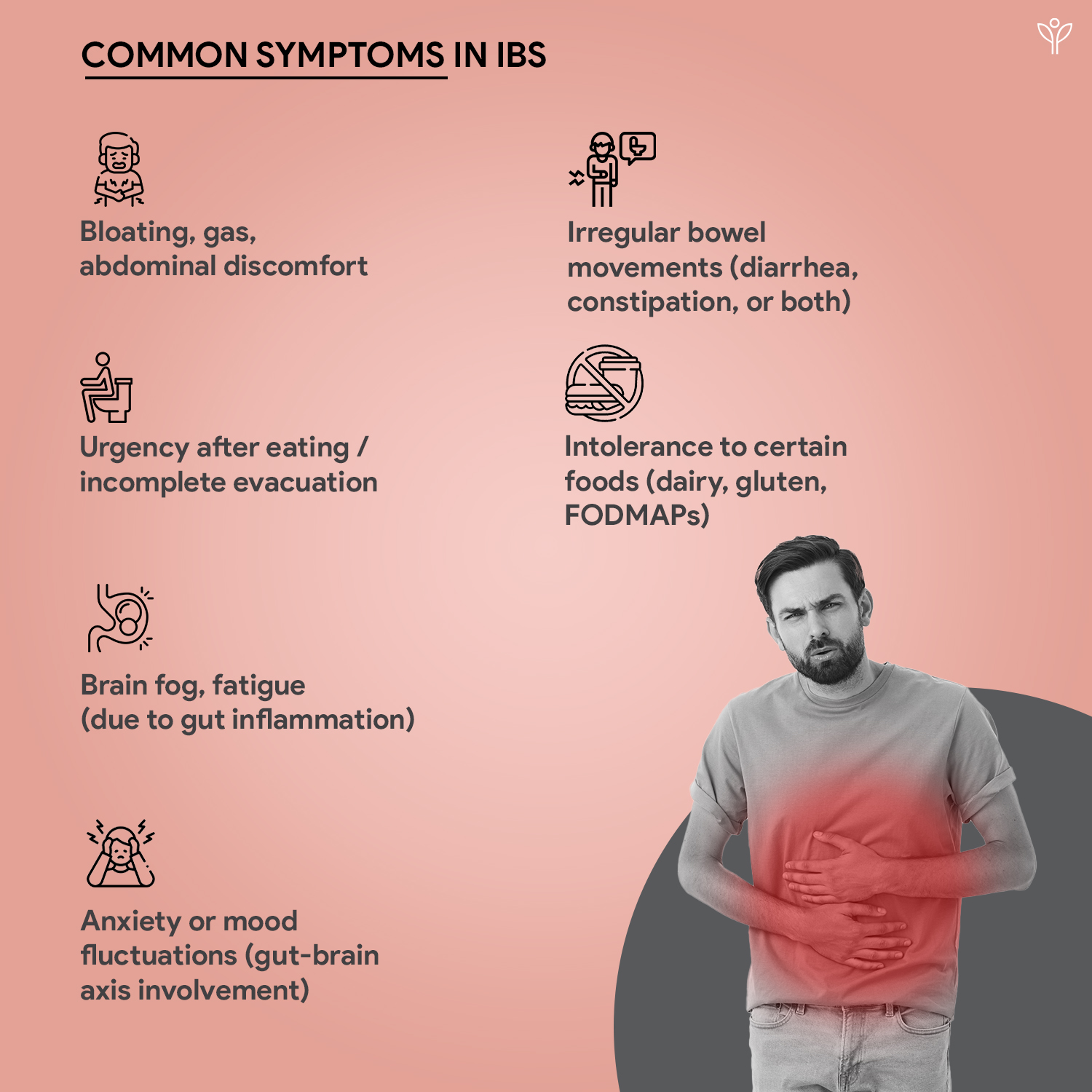

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by chronic abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits in the absence of identifiable structural or biochemical abnormalities (Latif et al., 2020; Mayer, 2008). It affects 10–20% of adults and adolescents worldwide, with women being disproportionately affected—14–24% in females and 5–19% in males (Coss-Adame & Rao, 2014; Longstreth et al., 2006; Al-Attar, 2020).

IBS is diagnosed using the ROME IV Criteria, which defines IBS as:

• Recurrent abdominal pain, at least 1 day per week for the last 3 months, associated with two or more of the following:

• Related to defecation

• Associated with change in stool frequency

• Associated with change in stool form (Ng et al., 2023)

What we have in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Reference

Alammar, N., Wang, L., Saberi, B., Nanavati, J., Holtmann, G., Shinohara, R. T., & Mullin, G. E. (2019). The impact of peppermint oil on the irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of the pooled clinical data. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-018-2409-0

Coss‐Adame, E., & Rao, S. S. C. (2014). Brain and Gut Interactions in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: New Paradigms and New Understandings [Review of Brain and Gut Interactions in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: New Paradigms and New Understandings]. Current Gastroenterology Reports, 16(4). Springer Science+Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-014-0379-z

Ferreira, A. I., Garrido, M., & Castro-Poças, F. (2019). Irritable Bowel Syndrome: News from an Old Disorder [Review of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: News from an Old Disorder]. GE Portuguese Journal of Gastroenterology, 27(4), 255. Karger Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1159/000503757

Holtmann, G., Ford, A. C., & Talley, N. J. (2016). Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. The Lancet. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 1(2), 133. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(16)30023-1

Karantanos, T., Markoutsaki, T., Gazouli, M., Anagnou, N. P., & Karamanolis, D. G. (2010). Current insights into the pathophysiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gut Pathogens, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-4749-2-3

Latif, A., Memon, F. A., & Asad, M. (2020). Irritable Bowel Syndrome in a Population of a Developing Country: Prevalence and Association. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8112

Longstreth, G. F., Thompson, W., Chey, W. D., Houghton, L. A., Mearin, F., & Spiller, R. E. (2006). Functional Bowel Disorders [Review of Functional Bowel Disorders]. Gastroenterology, 130(5), 1480. Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061

Mayer, E. A. (2008). Irritable Bowel Syndrome [Review of Irritable Bowel Syndrome]. New England Journal of Medicine, 358(16), 1692. Massachusetts Medical Society. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmcp0801447

Mayer, E. A., Ryu, H. J., & Bhatt, R. R. (2023). The neurobiology of irritable bowel syndrome [Review of The neurobiology of irritable bowel syndrome]. Molecular Psychiatry, 28(4), 1451. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-01972-w

Ng, Q. X., Yau, C. E., Yaow, C. Y. L., Chong, R. I. H., Chong, N. Z.-Y., Teoh, S. E., Lim, Y. L., Soh, A. Y. S., Ng, W. K., & Thumboo, J. (2023). What Has Longitudinal ‘Omics’ Studies Taught Us about Irritable Bowel Syndrome? A Systematic Review [Review of What Has Longitudinal ‘Omics’ Studies Taught Us about Irritable Bowel Syndrome? A Systematic Review]. Metabolites, 13(4), 484. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo13040484

Shaikh, S. D., Sun, N., Canakis, A., Park, W. Y., & Weber, H. C. (2023). Irritable Bowel Syndrome and the Gut Microbiome: A Comprehensive Review [Review of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and the Gut Microbiome: A Comprehensive Review]. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(7), 2558. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12072558